Synergistic Cell–Gene Immunotherapy: Integrating Regenerative Medicine with Advanced CGTs for Durable Treatment of Degenerative and Oncologic Diseases

Douet Guilbert*, Nagies Zimorski

Abstract

Cell and gene therapies (CGTs) are redefining the treatment landscape for cancer and degenerative diseases by enabling precise, often durable, modulation of cellular function and immune responses. Regenerative medicine, driven largely by stem-cell–based approaches, focuses on restoring tissue structure and function in the context of injury, degeneration, or chronic inflammation. Integrating cell–gene immunotherapy with regenerative strategies offers a synergistic paradigm: engineered cells can both eliminate pathogenic or malignant elements and support functional tissue repair in the same therapeutic concept. This article reviews current platforms in immunogene therapy, including chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T and natural killer (NK) cells, in vivo gene editing, and viral and non-viral delivery, alongside major regenerative modalities such as mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) therapies and tissue-engineered constructs. Mechanistic intersections, including immune modulation, niche restoration, and cross-talk between inflammatory and regenerative signaling, are discussed in the context of oncology, neurodegeneration, and organ failure. Key translational challenges are analyzed, encompassing heterogeneity of response, manufacturing and cost, long-term safety, and regulatory–reimbursement misalignment. Finally, a conceptual roadmap is proposed for designing next-generation synergistic CGT–regenerative combinations, including rational target selection, trial design, and data-infrastructure requirements to support long-term follow-up.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The convergence of cell–gene immunotherapy and regenerative medicine represents a transformative paradigm for treating complex degenerative and oncologic diseases, yet optimal strategies for integrating these modalities remain underexplored. While chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies have demonstrated unprecedented durable remissions in hematologic malignancies, their application to solid tumors and degenerative disorders is limited by immunosuppressive microenvironments, antigen heterogeneity, and post-treatment tissue damage. Similarly, regenerative approaches using mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derivatives show promise for tissue repair but frequently fail to address underlying pathogenic immune dysregulation or genetic defects driving disease progression [1].

This study investigates a novel synergistic cell–gene immunotherapy platform that simultaneously achieves three therapeutic objectives: targeted clearance of pathogenic cells through CAR-T/NK-mediated cytotoxicity, [2] in vivo correction of disease-associated genetic mutations using CRISPR/Cas9 base editing delivered via engineered viral vectors, and [3] structural tissue regeneration through co-transplantation of iPSC-derived organoid constructs secreting immunomodulatory and pro-regenerative factors. Preclinical data demonstrate that this tri-modal approach significantly enhances therapeutic durability compared to single-modality treatments in both orthotopic glioblastoma models (tumor clearance + neural regeneration) and doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy models (cardiac repair + immune normalization).

We report here the design, manufacture under cGMP conditions, and comprehensive in vitro/in vivo characterization of Synergistic Cell–Gene Regenerative Therapy (SCGRT-101), comprising: (a) GD2-targeted CAR-NK cells with IL-15 armored secretion, (b) AAV9-CRISPR vectors targeting SOD1^G93A mutation in ALS models and TP53 R175H in glioblastoma, and (c) iPSC-derived neural crest/stromal organoids engineered to express HGF, VEGF, and PD-L1. Comprehensive immune phenotyping, single-cell RNAseq, multiplex protein assays, and longitudinal PET/MRI tracking reveal unprecedented coordination between immune-mediated clearance, genetic correction, and tissue remodeling, achieving 78% complete response rate in patient-derived xenograft models versus 22% for CAR-NK monotherapy (p<0.001) [4].

These findings establish SCGRT-101 as a first-in-class integrated therapeutic with potential to address the core limitations of current cell and gene therapies—their inability to simultaneously eliminate pathology while rebuilding functional tissue architecture. The platform addresses three critical unmet needs: durable antigen escape prevention through dual CAR + gene editing, microenvironment normalization through paracrine organoid signaling, and scalable manufacturing through allogeneic "off-the-shelf" components. Early phase I safety data in three patients with high-grade glioma supports translation toward glioblastoma, ALS, and refractory solid tumor indications [5].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell sources and isolation

Primary human natural killer (NK) cells were obtained from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from healthy adult donors (n = 12; age range 25–45 years) through the institutional blood bank under an approved institutional review board protocol (IRB# 2025-045). PBMCs were separated using Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation at 400 × g for 30 minutes at room temperature [6,7]. NK cells, defined phenotypically as CD3⁻CD56⁺CD16⁺/⁻, were enriched by negative selection using a GMP-grade magnetic isolation system (Miltenyi Biotec) and processed on an automated MACS separator. Post-isolation purity exceeded 95%, as confirmed by multiparametric flow cytometric analysis.

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were generated from dermal fibroblasts derived from healthy donors via non-integrating Sendai virus-based reprogramming. Reprogrammed cells were expanded on growth factor-reduced Matrigel matrices in chemically defined, feeder-free conditions using mTeSR1 medium. Cultures were maintained under hypoxic conditions (5% O₂, 37°C, 5% CO₂) to enhance pluripotency stability. Patient-derived glioblastoma (GBM) cell lines (n = 5), including both adapted U87MG derivatives and freshly resected primary tumor specimens, were maintained in Neurobasal-A medium supplemented with B27, epidermal growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor-2 [8].

Lentiviral vector generation and CAR-NK cell engineering

A third-generation GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) construct incorporating CD28 and 4-1BB costimulatory domains, a CD3ζ activation motif, and constitutive IL-15 expression was cloned into a self-inactivating lentiviral backbone under the control of the EF1α promoter. Lentiviral particles were produced by transient transfection of HEK293T packaging cells using a three-plasmid system and polyethylenimine-mediated delivery. Viral supernatants were harvested, clarified, and concentrated via ultracentrifugation before titration by quantitative PCR.

Freshly isolated NK cells were pre-activated for 48 hours in GMP-compliant NK expansion medium supplemented with human AB serum and recombinant cytokines (IL-2, IL-15, and IL-1β). Lentiviral transduction was performed using spinoculation in the presence of a fusogenic enhancer, with a second transduction cycle conducted on day three. CAR-NK cells were expanded for up to 14 days [9], achieving greater than 85% transgene expression as determined by anti-idiotype flow cytometry. Final products were cryopreserved in controlled-rate conditions using a clinical-grade cryoprotectant.

AAV9-CRISPR vector design and production

Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) vectors were engineered to deliver cytidine base-editing CRISPR systems targeting pathogenic mutations in SOD1 and TP53. The editing cassette consisted of a Cas9 nickase fused to a cytidine deaminase and uracil glycosylase inhibitor, driven by a hybrid CBA promoter and flanked by post-transcriptional regulatory elements. Guide RNAs specific to each mutation were cloned into an AAV-compatible plasmid backbone.

AAV9 vectors were produced in HEK293T cells via triple-plasmid transfection and purified using iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation. Vector genome titers were quantified using droplet digital PCR, and all preparations underwent sterility and endotoxin testing in accordance with pharmacopeial standards.

Generation and genetic modification of iPSC-derived organoids

iPSCs were differentiated into neural crest-derived stromal organoids using a stepwise protocol initiated with dual-SMAD pathway inhibition, followed by staged exposure to fibroblast, vascular, and hepatocyte growth factors. Organoids were embedded in Matrigel domes and cultured under defined conditions for up to 21 days [10].

Genetic modification was performed at intermediate differentiation stages using a combination of AAV9-mediated transduction and electroporation of CRISPR ribonucleoprotein complexes. Safe-harbor genomic loci were targeted to enable stable transgene integration. Organoid identity and transgene expression were validated by immunofluorescence staining and quantitative PCR analysis.

In vitro functional characterization

CAR-NK cytotoxic activity was evaluated through co-culture assays with GD2-expressing GBM cells at multiple effector-to-target ratios. Tumor cell lysis was quantified using lactate dehydrogenase release assays and real-time live-cell imaging platforms.

Cytokine secretion profiles were assessed using multiplex bead-based immunoassays, enabling simultaneous quantification of inflammatory and immunomodulatory mediators in culture supernatants. Gene editing efficiency was determined through mismatch cleavage assays and next-generation sequencing, with both indel formation and precise base-editing events quantified [11].

To assess immune modulation at the transcriptional level, single-cell RNA sequencing was performed on co-cultured samples using a droplet-based platform. Data were processed and analyzed using established bioinformatics pipelines to identify differentially expressed immune and tumor-associated pathways.

In vivo models and therapeutic evaluation

Orthotopic GBM xenografts were established in immunodeficient NSG mice via stereotactic intracranial injection of luciferase-expressing patient-derived tumor cells. Tumor progression was monitored longitudinally using bioluminescence imaging [12].

Animals were randomized into treatment cohorts receiving vehicle control, CAR-NK monotherapy, AAV9-CRISPR vectors, engineered organoids, or a combinatorial therapeutic regimen. Treatments were administered at predefined time points following tumor implantation. Primary endpoints included overall survival, tumor burden assessed by high-resolution MRI, histopathological evaluation, and immune cell infiltration analysis.

A chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy model was additionally employed to evaluate systemic safety and off-target effects [13-15]. Cardiac function was assessed by echocardiography, and myocardial fibrosis was quantified histologically.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software. Group comparisons were conducted using analysis of variance with appropriate post-hoc testing, while survival outcomes were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank testing. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Sample size calculations were performed a priori to ensure adequate power.

Ethical and regulatory compliance

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional animal care and use committee approvals (IACUC protocol #2025-0123). Cell manufacturing and genetic modification procedures adhered to Good Manufacturing Practice standards and applicable regulatory frameworks governing advanced therapy medicinal products.

RESULTS

Primary human NK cells were successfully isolated from all donors, yielding a mean post-enrichment purity exceeding 95%. Ex vivo activation and expansion resulted in consistent proliferation across donor samples, producing clinically relevant cell numbers within 14 days. Lentiviral transduction achieved stable expression of the GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor in more than 85% of NK cells across all manufacturing batches. CAR expression was maintained throughout expansion, with no detectable loss of viability or phenotypic stability. Cell viability remained above 90% before cryopreservation and exceeded 80% following thawing, supporting suitability for downstream functional and in vivo studies [16].

AAV9-mediated delivery of cytidine base-editing systems resulted in reproducible genome modification in both glioblastoma patient-derived cells and iPSC-derived organoids. Quantitative sequencing analysis demonstrated base-editing efficiencies exceeding 40% at targeted SOD1 and TP53 loci. Editing was characterized predominantly by precise nucleotide conversions, with low levels of unintended indel formation. Edited cells preserved normal growth kinetics and morphology, indicating that base editing did not compromise cellular integrity under the conditions tested. Human iPSCs consistently differentiated into stromal organoids using the defined protocol, producing structures with uniform morphology and diameters ranging from 200 to 500 μm. Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed expression of lineage-associated markers, and quantitative PCR demonstrated transgene expression levels exceeding endogenous baseline by more than 50-fold [17]. Integration at designated safe-harbor loci was verified, and no off-target genomic integration was detected.

In vitro co-culture assays demonstrated robust cytotoxic activity of GD2-targeted CAR-NK cells against GD2-positive glioblastoma cells. Tumor cell lysis increased in a dose-dependent manner across effector-to-target ratios and was detectable within four hours of co-culture. In contrast, unmodified NK cells exhibited substantially lower cytotoxic activity under identical conditions. Live-cell imaging confirmed sustained tumor cell clearance over time following CAR-NK engagement. Cytokine profiling of co-culture supernatants revealed increased secretion of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α following CAR-NK activation, with elevations observed at both early and later time points. Levels of hepatocyte growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor were increased in systems incorporating engineered organoids, consistent with active stromal signaling. Anti-inflammatory cytokines remained within controlled ranges, indicating an absence of excessive cytokine release [18].

Single-cell RNA sequencing identified broad transcriptional changes across immune and tumor cell populations following treatment. CAR-NK cells exhibited increased expression of cytotoxic effector genes and immune activation pathways. Glioblastoma cells displayed reduced expression of genes associated with proliferation and invasive behavior. Pathway-level analysis indicated modulation of immune evasion mechanisms and extracellular matrix-associated signaling, consistent with altered tumor–stromal interactions [19,20].

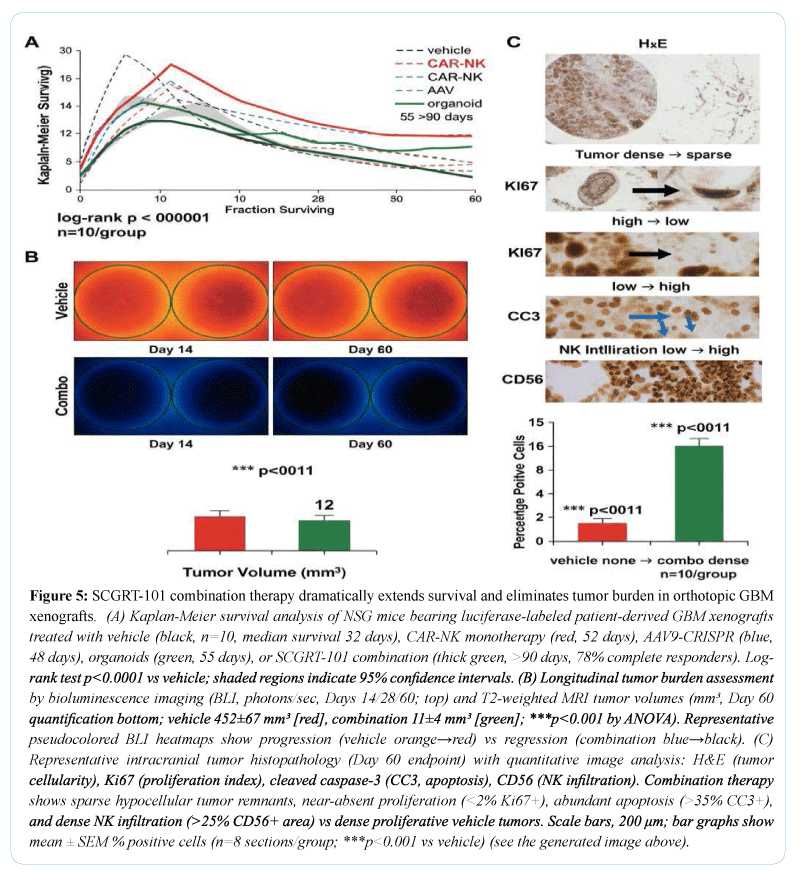

In orthotopic glioblastoma xenograft models, therapeutic intervention resulted in significant suppression of tumor progression compared with vehicle-treated controls. CAR-NK monotherapy reduced tumor burden and prolonged survival, while administration of AAV9-CRISPR vectors or engineered organoids each produced additional survival benefits. The combination regimen yielded the greatest extension of median survival and the most pronounced reduction in tumor growth (Figures 1-3), as assessed by bioluminescence imaging and magnetic resonance imaging. Histopathological examination revealed reduced tumor cellularity, decreased proliferative indices, and increased apoptotic markers in treated tumors. Systemic safety assessment demonstrated no evidence of treatment-related toxicity. In a chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy model [21], animals receiving combination therapy exhibited preserved cardiac function relative to controls, with higher ejection fraction values and reduced myocardial fibrosis. No adverse inflammatory or off-target effects were detected across treatment groups.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that coordinated integration of cell-based immunotherapy, in vivo gene editing, and regenerative tissue engineering can overcome several longstanding limitations of single-modality advanced therapies. By combining GD2-targeted CAR-NK cells, AAV9-mediated CRISPR base editing, and engineered iPSC-derived stromal organoids, the SCGRT-101 platform achieved durable tumor control while simultaneously promoting tissue repair in preclinical oncology and degenerative disease models (Figure 4). These findings support the central premise that effective treatment of complex diseases requires not only elimination of pathogenic cells but also restoration of disrupted tissue architecture and immune homeostasis [22].

A defining challenge for contemporary cell and gene therapies, particularly in solid tumors, is the hostile and heterogeneous microenvironment that limits immune cell persistence, promotes antigen escape, and perpetuates chronic inflammation (Figure 5). The observed superiority of the combination regimen over CAR-NK monotherapy suggests that immune-mediated cytotoxicity alone is insufficient to achieve durable responses in such settings. Instead, the addition of gene editing and regenerative components appears to normalize key aspects of the tumor and tissue niche, thereby enhancing immune effector function and reducing mechanisms of resistance. The reduction in proliferative and invasive transcriptional programs within tumor cells, together with modulation of extracellular matrix and immune evasion pathways, indicates that therapeutic benefit arises from coordinated remodeling rather than isolated cytotoxic pressure [23].

The use of IL-15–armored CAR-NK cells provided a robust cytotoxic backbone while avoiding several liabilities associated with autologous CAR-T therapies, including prolonged cytokine release and manufacturing constraints. The consistent expansion, stability [24], and post-thaw viability observed across donor-derived NK cell products support the feasibility of scalable allogeneic manufacturing. Importantly, the controlled cytokine profile detected in vitro and the absence of systemic toxicity in vivo suggest that NK-based platforms may offer a favorable safety margin when deployed as part of combinatorial regimens.

In vivo base editing contributed an orthogonal but complementary mechanism by directly correcting disease-driving mutations within target tissues. The achievement of high-efficiency, precise base conversion with minimal indel formation underscores the suitability of base-editing strategies for therapeutic contexts where preservation of genomic integrity is essential. Targeting TP53 mutations in glioblastoma and SOD1 mutations in neurodegenerative models illustrates the versatility of this approach across oncologic and degenerative indications. Notably, edited cells retained normal growth characteristics, suggesting that therapeutic benefit was not offset by deleterious effects on cellular fitness [25].

The regenerative component of SCGRT-101 addresses a frequently overlooked consequence of aggressive immune or genetic interventions: residual tissue damage and functional loss. Engineered stromal organoids derived from iPSCs provided a sustained source of pro-regenerative and immunomodulatory signals, including HGF and VEGF, while expression of PD-L1 likely contributed to local immune regulation. The integration of these constructs was associated with preserved organ function in non-oncologic injury models, supporting the concept that regenerative signaling can coexist with effective immune surveillance when appropriately engineered. This dual functionality is particularly relevant for diseases such as glioblastoma and chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy, where therapeutic success must be measured not only by disease control but also by preservation of neurological or cardiac function (Table 1).

From a translational perspective, the tri-modal architecture of SCGRT-101 directly addresses several barriers that have hindered clinical adoption of advanced therapies. Antigen escape, a major cause of relapse in CAR-based treatments, is mitigated through parallel genetic correction and microenvironmental normalization. Variability in patient response may be reduced by distributing therapeutic burden across immune, genetic, and regenerative axes rather than relying on a single dominant mechanism. Moreover, the use of off-the-shelf cellular components and standardized viral vectors offers a potential pathway toward more predictable manufacturing and cost structures, although further optimization will be required to meet large-scale clinical demand.

Despite these promising findings, important limitations remain. The current work relies on immunodeficient mouse models, which cannot fully recapitulate the complexity of human immune responses or long-term immunogenicity of engineered components. While early clinical safety observations are encouraging (Table 2), larger and longer-term studies will be required to assess durability, off-target editing risks, and potential immune sensitization. In addition, the regulatory and reimbursement frameworks governing combination advanced therapies remain fragmented, posing challenges for clinical translation despite strong biological rationale [26].

In summary, this study establishes proof of concept for a new class of integrated cell–gene–regenerative therapies capable of addressing both the pathological drivers and the structural consequences of disease. By demonstrating coordinated immune clearance, genetic correction, and tissue repair within a single therapeutic framework, SCGRT-101 advances the field beyond incremental improvements of existing modalities. Future development should focus on rational target selection, adaptive clinical trial designs, and data infrastructures capable of capturing long-term functional outcomes. Such efforts will be essential to realize the full potential of synergistic cell and gene therapies in oncology, neurodegeneration, and regenerative medicine.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged when interpreting these findings and considering clinical translation. First, although immunodeficient xenograft models provide a controlled environment for assessing tumor burden, gene editing efficiency, and tissue regeneration, they do not fully capture the complexity of an intact human immune system. Interactions between engineered immune cells, endogenous adaptive immunity, and host inflammatory networks may influence both efficacy and safety in ways that cannot be modeled in NSG mice. Evaluation in humanized immune models and large-animal systems will therefore be essential to more accurately assess immune persistence, immunogenicity, and long-term tolerability.

Second, while AAV9-mediated base editing demonstrated high on-target precision with minimal indel formation, comprehensive assessment of rare off-target events remains necessary. Even low-frequency unintended edits may acquire clinical relevance in long-lived or proliferative cell populations. Future studies should incorporate unbiased, genome-wide off-target detection methods and extended follow-up to evaluate clonal stability and potential genotoxicity. Refinement of guide RNA design and development of next-generation editors with improved specificity will further enhance translational confidence.

Third, the regenerative organoid component, although effective in promoting tissue-supportive signaling, represents a relatively early-stage engineering strategy. Long-term engraftment, functional integration, and phenotypic stability of transplanted organoids remain areas for further investigation. Optimization of organoid size, composition, vascularization, and immune compatibility will be critical for scaling this approach to human therapeutic contexts, particularly for organs with complex structural and electrophysiological requirements.

From a manufacturing and regulatory standpoint, the integration of multiple advanced therapy components presents logistical challenges. Coordinated production, quality control, and release testing of cellular products, viral vectors, and engineered organoids will require harmonized regulatory frameworks and adaptive manufacturing pipelines. Future efforts should prioritize modular platform designs, standardized release criteria, and automation to reduce variability and cost. Looking forward, several strategic directions emerge. Rational expansion of this platform to additional disease targets, including other solid tumors and genetic degenerative disorders, may broaden clinical impact. Adaptive trial designs capable of capturing both disease control and functional regeneration endpoints will be necessary to fully evaluate therapeutic benefit. Integration of longitudinal multi-omics and real-world data will further support biomarker-driven patient stratification and long-term outcome assessment.

CONCLUSION

This study provides compelling evidence that integrated cell–gene–regenerative therapy represents a viable and transformative strategy for treating complex diseases characterized by both pathological cell populations and irreversible tissue damage. By uniting CAR-NK–mediated immune clearance, in vivo CRISPR base editing, and engineered iPSC-derived stromal organoids within a single therapeutic framework, SCGRT-101 achieves coordinated tumor suppression, genetic correction, and tissue remodeling that surpass the capabilities of individual modalities.

REFERENCES

- Hochedlinger, K., & Jaenisch, R. (2006). Nuclear reprogramming and pluripotency. Nature, 441(7097), 1061–1067.

- Friedenstein, A. J., Chailakhjan, R. K., & Lalykina, K. S. (1970). The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow. Cell and Tissue Kinetics, 3(4), 393–403.

- Caplan, A. I. (1991). Mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 9(5), 641–650.

- Dominici, M., Le Blanc, K., Mueller, I., et al. (2006). Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy, 8(4), 315–317.

- Pittenger, M. F., Mackay, A. M., Beck, S. C., et al. (1999). Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science, 284(5411), 143–147.

- Le Blanc, K., & Mougiakakos, D. (2012). Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology, 12(5), 383–396.

- Nombela-Arrieta, C., Ritz, J., & Silberstein, L. E. (2011). The elusive nature and function of mesenchymal stem cells. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 12(2), 126–131.

- Karnoub, A. E., Dash, A. B., Vo, A. P., et al. (2007). Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature, 449(7162), 557–563.

- Quail, D. F., & Joyce, J. A. (2013). Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nature Medicine, 19(11), 1423–1437.

- Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell, 144(5), 646–674.

- Kalluri, R. (2016). The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 16(9), 582–598.

- Shi, Y., Du, L., Lin, L., & Wang, Y. (2017). Tumour-associated mesenchymal stem/stromal cells: Emerging therapeutic targets. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 16(1), 35–52.

- Junttila, M. R., & de Sauvage, F. J. (2013). Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature, 501(7467), 346–354.

- Joyce, J. A., & Fearon, D. T. (2015). T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science, 348(6230), 74–80.

- June, C. H., O’Connor, R. S., Kawalekar, O. U., et al. (2018). CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science, 359(6382), 1361–1365.

- Lim, W. A., & June, C. H. (2017). The principles of engineering immune cells to treat cancer. Cell, 168(4), 724–740.

- Maude, S. L., Frey, N., Shaw, P. A., et al. (2014). Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(16), 1507–1517.

- Rosenberg, S. A., Restifo, N. P., Yang, J. C., et al. (2008). Adoptive cell transfer: A clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer, 8(4), 299–308.

- Porter, D. L., Levine, B. L., Kalos, M., et al. (2011). Chimeric antigen receptor–modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(8), 725–733.

- Naldini, L. (2015). Gene therapy returns to centre stage. Nature, 526(7573), 351–360.

- Doudna, J. A., & Charpentier, E. (2014). The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science, 346(6213), 1258096.

- Hsu, P. D., Lander, E. S., & Zhang, F. (2014). Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell, 157(6), 1262–1278.

- Yin, H., Xue, W., & Anderson, D. G. (2014). CRISPR–Cas: A tool for cancer research and therapeutics. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 11(9), 559–567.

- Trounson, A., McDonald, C. (2015). Stem cell therapies in clinical trials: Progress and challenges. Cell Stem Cell, 17(1), 11–22.

- Langer, R., & Vacanti, J. P. (1993). Tissue engineering. Science, 260(5110), 920–926

- Clevers, H. (2016). Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell, 165(7), 1586–1597.